Book Review by Judy Dederick

A Girl is a Body of Water

by Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi, Tovah Ott, et al. (Author)

Think about yourself as a young (American) adolescent. Did you wish you had a different mother? Were you afraid of being caught in a lie and punished? How much time did you spend thinking about what would happen if you said “Hi” to the classmate you had a crush on?

Each of those intense feelings was grounded in a cultural context: you knew your angry thought would not hurt your mother and might well amuse her. If you intentionally did something bad–maybe to test a limit—you knew you would be “grounded” or some other punishment, after which everything would be ok again. And all of your friends had different ideas about how to get attention from a crush—it was endlessly discussed, and there were no rules.

Kirabo, in A Girl Is A Body of Water, faces those and myriad other normal teenage feelings, but her underlying beliefs about them are very different. In Kirabo’s traditional family in rural Uganda, everyone believes that people can be harmed or changed by witches, so you have the power to ask a witch for help. If something bad happens, everyone wonders if a witch caused it and why. Or, a wife can be dismissed and sent away by the elders and other wives in the extended family and forced to leave her children behind. So, it is angry feelings are thought to be very dangerous. Similarly, if you do something considered bad, spirits of all kinds might make you fall into a river or a fire. In addition to being punished by elders–spirits are everywhere and powerful too. And if you have a crush on an agemate, your family must approve of that person based on that child’s family, their social class, their financial status, and so on, and only with that approval and watched by the family can you engage in ritualized initiatives for a relationship. We often think that we live in a dangerous world; I could hardly fathom how Kirabo navigated hers, so different from ours.

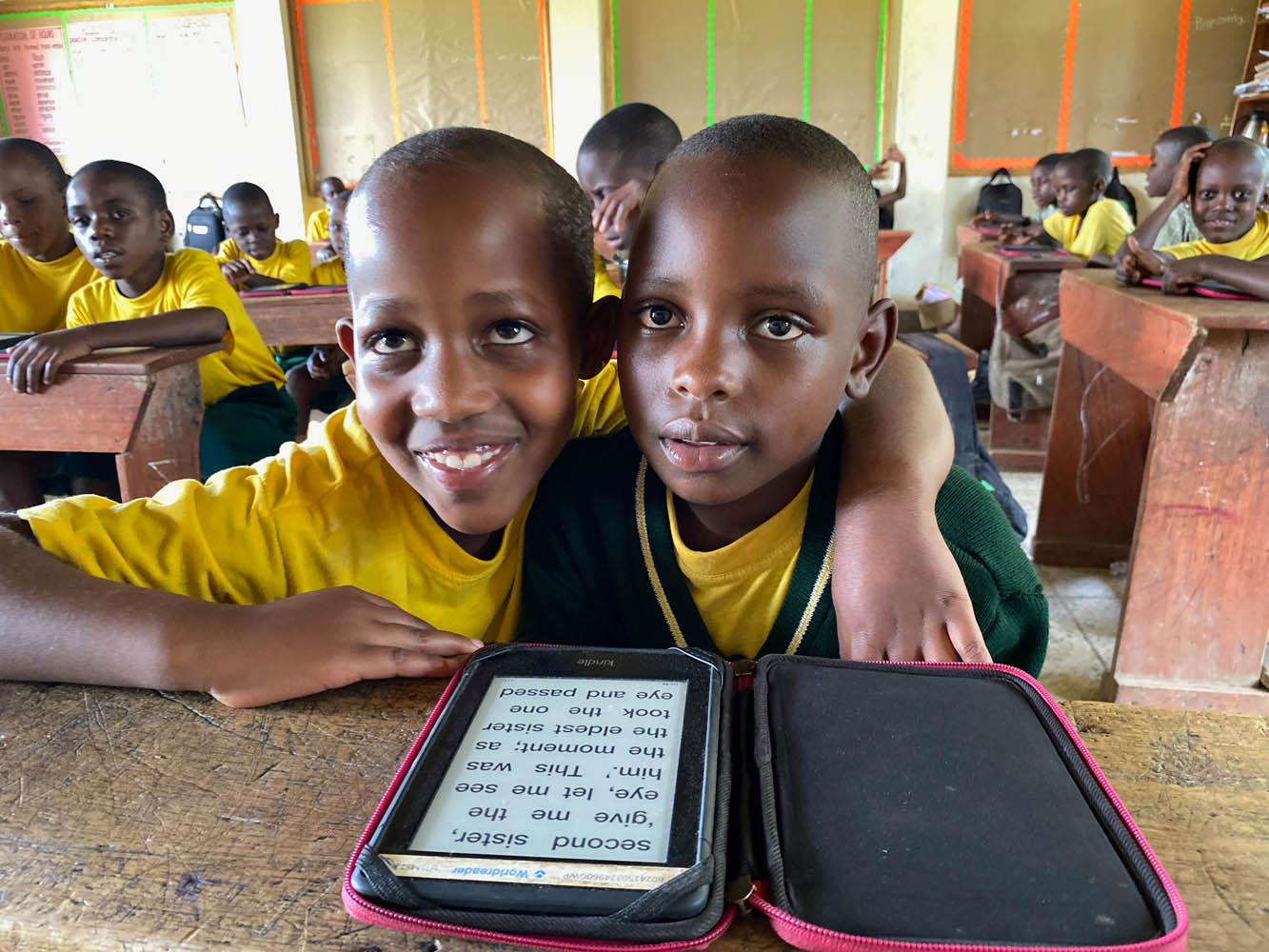

I loved reading about Kirabo’s life and development, what happened, and how she understood it. It is a coming-of-age story from a different world, and while getting to know Kirabo and her friends and family, I was immersed in the stories, legends, and assumptions of traditional Ugandan culture. I like to think about the children in Real Partners Uganda’s care and wonder what assumptions they make about their lives and their good fortune. I wonder what they think about me, a far-away “sponsor.” How do they think our lives work, and why?